Kazakhstan’s civil nuclear industry, the Belt and Road Initiative, and the prospect of Russia-China competition

Special Issue #2

In this issue:

How did Kazakhstan’s civil nuclear industry originate?

What were the industry’s successes and failures in the pursuit of international cooperation?

Do legacy ties remain between the Russian and Kazakhstani civil nuclear industries?

Why is Kazakhstan building a new nuclear power plant (NPP)?

What are the main challenges of NPP construction, and why did Kazakhstan’s previous attempts fail?

Would a NPP deal with Rosatom render Kazakhstan vulnerable to dependencies, thereby giving Russia greater geopolitical leverage?

Is China’s involvement in Kazakhstan’s civil nuclear sector linked to the Belt and Road Initiative?

Are common critiques associated with the Belt and Road – such as “debt traps” and exploitative resource extraction – evident in China’s engagement of the Kazakhstani civil nuclear sector?

To what extent is the Kazakhstani nuclear sector becoming an arena of Russia-China competition?

Now that the West has imposed unprecedented sanctions on Russia, will Kazakhstan face challenges maintaining its civil nuclear ties with entities on both sides of the geopolitical divide?

Feel free to reproduce any part of the following analysis elsewhere with a link to this original post. Or email yp168@georgetown.edu for research collaboration.

Kazakhstan has announced new plans to construct a nuclear power plant (NPP) in the country to address future energy shortfalls. According to official representatives, four foreign reactor technology suppliers are currently being considered for the multi-billion-dollar project, including China’s CNNC, France’s EDF, South Korea’s KHNP, and Russia’s Rosatom. In a geopolitically delicate region like Central Asia, this is a troublesome mix of competitors. Given the size of the financial investment typically required and the inherent security sensitivity of nuclear infrastructure, nuclear energy deals between countries almost always involve state actors standing behind ostensibly commercial entities. Consequently, competition over such deals often becomes geopolitically charged.

Kazakhstan is not only a key Russian partner in the Collective Security Treaty Organization and Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), but also a critical link along China’s Silk Road Economic Belt – part of the better-known Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). At the same time, the Kazakhstani government, in pursuit of a multi-vector foreign policy, has fostered cooperative relations with Western states, adding further complexity to the country’s geopolitical orientation. As Western states look to reduce their dependence on Russian uranium supplies, Kazakhstan, with its leading position in the global uranium market, becomes an increasingly attractive source of the key input in nuclear fuel. The challenge for the Central Asian state is to navigate its complex circumstances to extract benefit without disrupting the increasingly delicate balance of geopolitical forces surrounding it.

1. First things first – how did Kazakhstan’s civil nuclear industry originate?

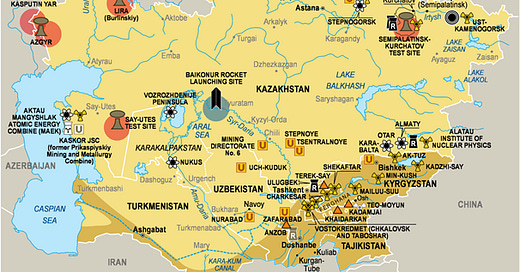

When the Soviet Union broke up in 1991, Kazakhstan inherited a sizeable assembly of nuclear assets, both civilian and military. Thanks to a series of nonproliferation efforts involving international actors, the military assets were quickly dismantled. Previously deployed nuclear warheads were removed, and the notorious nuclear test facility at Semipalatinsk finally shut its gates. The civilian assets, on the other hand, were retained.

Endowed with abundant uranium resources, Kazakhstan supplied natural uranium and fuel pellets for the entire Soviet civil nuclear industry before 1991. However, those processes of the nuclear fuel cycle that were more technically complex and further up the value chain – such as conversion, enrichment, and assembly fabrication* – had always been monopolized by Russian enterprises. As Kazakhstan sought to further develop its inherited nuclear industry following independence, it not only strove to become the largest global supplier of low-value uranium products – which it did – but also aimed to climb up the value chain through the acquisition of nuclear fuel processing technologies. The only path to do so was to develop joint ventures (JVs) with foreign entities, trading uranium access for technology transfer. This has been the strategy of Kazakhstan’s national nuclear operator, Kazatomprom, since the 2000s.

* For those unfamiliar with the technical terms, the front end of the uranium fuel cycle consists of mining (digging the uranium ore out of the ground); milling (extracting the uranium from the ore, achieving a relatively pure U3O8 powder, also called yellow cake); conversion (turning the powder into uranium hexafluoride, or UF6, gas), enrichment (increasing the concentration of uranium-235 against uranium-238), and fuel fabrication (converting the UF6 gas back into solid pellets, packing them into fuel rods, and bundling the rods into assemblies to be inserted into a nuclear reactor). More details are available here.

The nuclear fuel cycle | Source: United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission

2. How was international cooperation conducted? What were the successes and failures?

Starting from the mid-2000s, Kazakhstan launched a concerted effort to broaden its international partnerships in order to modernize its nuclear industry. Although joint mining ventures were set up quickly, progress was slow on the transfer of high value-added technology. In order to acquire modernized uranium conversion capability, Kazatomprom signed a memorandum of understanding with Canada’s Cameco Corporation as early as 2007 to set up a new conversion plant – a deal which has been repeatedly mentioned since then but with little concrete follow-up. Also in 2007, Kazatomprom bought from Toshiba a 10% stake in U.S.-based Westinghouse, hoping to gain fuel fabrication technologies from the latter. The shares were sold ten years later, and technology transfer was never realized. Similarly, with Japan and France, Kazakhstan signed two separate deals to acquire the technologies and licenses to fabricate and export nuclear fuel assemblies – in 2007 and 2008, respectively. But over subsequent years, Japan has only licensed Kazakhstani uranium dioxide powder while little progress was made on the JV with France’s Areva, that is, until China’s state-owned nuclear energy corporation CGN stepped in with an offer to contribute half of the $147 million investment needed to launch a fuel fabrication plant at the Ulba complex using French technology.

As with other players in the international uranium market, CGN launched its activities in Kazakhstan in the mid-2000s, starting with joint uranium mining ventures before moving on to purchases of higher value-added uranium products such as fuel pellets. In December of 2014, CGN signed a framework agreement with Kazatomprom, followed by a commercial protocol one year later, to construct a facility for the fabrication of Framatome’s AFA 3G nuclear fuel assemblies for the CPR1000 reactors it operates in China.* Production began on November 10, 2021. The plant’s Framatome-licensed production capacity of 200 tU per year is sufficient to satisfy the fuel demand of up to eight 1000MW reactor units, with further expansion possible. Thus, Kazakhstan leveraged Chinese investment to acquire the technology to fabricate high value-added fuel assemblies of Western design, becoming one of a few countries in the world with assembly fabrication and export capacity.

* The CPR1000 uses French-designed fuel assemblies as it was adapted from the French M310 reactor design.

Commercial fuel assembly at the Ulba fabrication plant | Source: Ulba-FA/Ulba-TVS

3. What about Russia? Do legacy ties remain between the Russian and Kazakhstani civil nuclear industries?

Mutual dependencies between the Russian and Kazakhstani civil nuclear industries can be traced back to the Soviet period, when Kazakhstan, as previously mentioned, supplied uranium input products to Russian conversion, enrichment, and fuel assembly fabrication facilities. These supply chain ties as well as personnel connections have persisted to the present day, with one of the most illustrative examples being the sharing of enrichment capacity.

Constrained by its commitment to the nonproliferation of dual-use technologies, Kazakhstan did not make extensive efforts to develop indigenous enrichment capacity following independence. In order to secure supplies of low-enriched uranium (LEU) for its own nuclear industry, the country chose to acquire priority access to Russian enrichment services. In 2006, Kazakhstan established a Uranium Enrichment Center (UEC)* in partnership with Rosatom subsidiary TVEL. The original plan was to build additional enrichment capacity through the JV at the enrichment plant in the Russian city of Angarsk, but that plan was soon abandoned as uneconomical. The JV then focused on buying shares of existing Russian enrichment enterprises, eventually acquiring a 25% stake in the Urals Electrochemical Combine (UECC) and gaining access to 5 million SWU of its annual enrichment capacity. In early 2020, Kazatomprom announced it would sell its 50% interest in UEC minus one share due to market reasons, but the one share it retains will continue to give it guaranteed access to Russian enrichment services.

The Ural Electrochemical Combine | Source: Rosatom

Enrichment is not the only area where the Kazakhstani nuclear industry depends on its legacy ties with Russia. In fact, the countries have signed a series of agreements to take advantage of Soviet-era linkages and complementarities by integrating their civil nuclear industries. The scope of these agreements covers the entire nuclear fuel cycle. In addition, a significant number of Kazakhstan’s civil nuclear specialists are trained by Russia due to Soviet-era personnel and institutional legacies. Recent agreements on specialist training – such as the one signed earlier this year on the establishment of an Almaty campus by Russia’s National Research Nuclear University MEPhI – further cemented personnel ties.

Last but not least, Russia has been an important transit state for Kazakhstan’s uranium exports to Western markets. Although a Caspian route to the west and a Chinese route to the east exist as alternatives, much of Kazakhstan’s exported uranium is transported by rail to the port of St. Petersburg and shipped onward. Now, with sanctions having induced general logistics disruptions between Russia and Western countries, it is likely that Kazatomprom will seek to further diversify its export routes.

* The Uranium Enrichment Center (UEC) is not to be confused with the International Uranium Enrichment Center (IUEC), which Russia and Kazakhstan established as a JV to help the IAEA offer guaranteed LEU supplies to member states so they could securely develop their civil nuclear industries even without attaining – or being tempted to attain – domestic uranium enrichment capability. Under a 2007 agreement, a LEU reserve subject to distribution by the IAEA became available in the Russian city of Angarsk in 2010.

4. Why is Kazakhstan building a new nuclear power plant (NPP)?

Kazakhstan’s renewed NPP construction attempt is part of a broader strategy to address the electricity shortage the country and the general region are projected to face in the next decade. In January, 2021, President Tokayev gave an order to Kazakhstan’s government and national wealth fund Samruk-Kazyna to develop a 2035 energy balance plan to address the electricity shortage the country was predicted to face by 2027 and mitigate the country’s historical energy dependency on neighboring Central Asian states. Fully developed earlier this year, the plan envisions building a new NPP with the power of 2.4 GW, around one seventh of the 17.5 GW of new generation capacity to be built by 2035. While Kazakhstan does have an abundance of fossil fuels and ambitious renewable energy development objectives, nuclear power remains the only source of carbon-free baseload electricity. During his 2021 State of the Nation Address, Kazakhstani President Kassym-Jomart Tokaev instructed the government and Kazakhstan’s national wealth fund Samruk-Kazyna to “explore the possibility of developing safe and environmentally friendly nuclear energy in Kazakhstan.” “With the gradual decline of the era of coal,” the president said, “we will have to think about sources of reliable basic energy generation apart from renewables. There will already be a shortage of electricity in Kazakhstan by 2030. Global experience suggests that the most optimal solution is the peaceful atom.”

President Tokaev delivering the 2021 State of the Nation address | Source: Akorda.kz

Thereafter, a feasibility study on the new NPP began, scheduled to last until the end of 2022. The site for the potential construction was selected near Ulken, Almaty Region, in the southern part of the country. Among Kazakhstan’s northern, southern, and western grids, the southern one is in the greatest need for new generation capacity. In addition, Kazakhstan’s southern neighbors that are connected to it by grid will, according to some projections, experience increased energy demand in the future, making the export of electricity a promising prospect.

Apart from the energy security and decarbonization agendas, NPP construction also fits into the Kazakhstani civil nuclear sector’s long-term goal of acquiring advanced reactor technologies. In terms of value added, the generation and sale of electricity has the potential to be more profitable than the mining and processing of raw uranium and would arguably be a better use of the natural uranium endowment Kazakhstan possesses in abundance.

It is partly to that end that Kazatomprom has sought to acquire foreign reactor technologies through JVs and through construction deals, an example being the 2006 agreement between Kazatomprom and Rosatom subsidiaries Techsnabexport and Atomstroyexport to jointly design small and medium reactors both for domestic construction and for export to third countries. With a follow-up agreement being signed in 2010 to build a jointly designed reactor in Aqtau on the Caspian coast, the undertaking initially looked promising. But no project eventually came to fruition. In 2014, Kazakhstan signed another agreement with Russia for the construction of Russian-designed VVER reactors from 300MW in capacity at a site near Kurchatov. That project, too, was dropped, although a commercial entity – Kazakhstan Nuclear Power Plants LLP – was founded by the Kazakhstani sovereign wealth fund that same year, in accordance with a government action plan for NPP construction. That company is still very much active and just last year signed a memorandum of understanding with U.S.-based NuScale Power to deploy small modular reactors in Kazakhstan.

5. What are the main challenges faced by Kazakhstan as it aims for new NPP construction?

In the past, whether with Russian or U.S. partners, Kazakhstan has sought to develop and deploy reactors of small and medium capacity likely because there was not high enough demand for a full-scale NPP within any one region, and it was inefficient to transmit electricity over long distances across regions through the country’s relatively poor electricity grid. Now that the Kazakhstani government has opted to build a 2.4 GW (or 2,400 MW) NPP at one site, it remains to be seen whether and how the issue of transmission efficiency will be resolved.

With large NPP projects typically requiring massive investment over long time horizons, another issue is whether the budget and time schedule for construction can be met to address future electricity shortages in time. Among the Generation III reactor technologies currently on the market, most either remain unproven or have turned out to be much more expensive and time-consuming to build than originally anticipated. The Kazakhstani stakeholders have already excluded the United States and Japan for their lack of a proven reactor design. France’s EPR has experienced repeated delays and huge cost overruns in domestic construction, and a new, improved EPR design is still being finalized. As an alternative, Kazakhstan seems to be considering the ATMEA-1, the reactor design that was supposed to be built at Türkiye’s Sinop NPP but was eventually abandoned by the Turkish authorities due to the projected construction schedule and cost having become unacceptable. While KHNP (South Korea) does have a proven APR1400 design, the previous government’s policy to move away from nuclear energy caused a number of South Korean enterprises responsible for the manufacturing of NPP equipment to shift to other sectors. Their potential to restart manufacturing with minimal delays is yet to be seen.

Unless the Kazakhstani stakeholders decide to overlook the concerns enumerated above, then exactly two players are left with the relatively certain capability of completing the project on time and on budget, namely, Russia’s Rosatom and China’s CNNC. Both corporations are completely state-owned. In fact, both are successors of their respective states’ nuclear industry ministries and oversee both military and civilian nuclear applications. CNNC is under U.S. sanctions as a “Chinese military-industrial complex company” while sanctions against Rosatom are being discussed in Brussels. The geopolitical risks are clearly quite real.

As of now, Kazakhstan has announced only that the final vendor decision will be made in 2023 and that contractors from a group of countries will be involved rather than just a single one. Regardless of the vendor chosen, it will be imperative to finish the project as quickly and economically as possible given the urgent need for new generation capacity. Any delay would undermine energy security, and the Kazakhstani state is not rich enough to swallow billions of dollars in runaway construction costs, especially under the scrutiny of a general public whose patience with the word “nuclear” is thin to begin with. Indeed, the notorious nuclear weapons tests the Soviet military conducted at Semipalatinsk constitute part of Kazakhstan’s collective post-Soviet trauma. Environmentally damaging Soviet nuclear industry activities leading to irresponsible radioactive waste disposal have likewise created public sensitivity around the sector. All these sentiments can be readily mobilized by political actors to hinder the project. This is not even mentioning the potential controversy from involving Russian and Chinese state-owned enterprises in Kazakhstan’s critical infrastructure. There is already some domestic concern that Russia’s pursuit of a nuclear power project in Kazakhstan is aimed at extending its geopolitical influence or ensnaring the country in a “debt trap.”

A map from 2000 showing nuclear sites in Central Asia | Source: United Nations Environment Programme

The Semipalatinsk nuclear test site | Source: AFP/Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

It is partly for economic reasons and partly due to the public opinion obstacle that Kazakhstan’s prior attempts to construct domestic nuclear power facilities have failed to come to fruition. Indeed, Kazakhstan has been attempting to build its own NPP since the late 1990s. The idea of building a facility near Lake Balkhash was raised as early as 1997. When that first suggestion was abandoned, another NPP consisting of two Russian VBER-300 units was planned at Aqtau on the Caspian coast, where a Soviet BN-350 fast reactor operated for both desalination and power generation from 1973 to 1998. That plan, too, failed to move forward. Three years later, in 2009, Russia proposed the construction of a NPP near Kurchatov, in the area of Semipalatinsk. Even a memorandum on construction was signed in May of 2014, after the president of the republic issued instructions to the government to “agree on the location, investment sources, and construction schedule for a nuclear power plant” in the first quarter of the year. No construction activity followed. Despite the Russian government and Rosatom repeatedly signaling their readiness to move forward, the Kazakhstani stakeholders have demurred. While the government does seem committed this time to getting the project off the ground, it remains to be seen whether it is indeed serious enough to follow through, not least by overcoming the technical, commercial, and political challenges that hindered similar projects in the past.

6. Would a NPP deal with Russia or, for that matter, China, in fact render Kazakhstan vulnerable to financial, technological, or fuel supply dependencies to the detriment of its geopolitical autonomy?

The autonomy of Kazakhstan’s civil nuclear industry is well guarded by supply chain interdependence. As previously discussed, Kazakhstan is a major supplier of uranium products worldwide. The Russian nuclear fuel industry depends on Kazakhstan for supplies of natural uranium and fuel pellets. Thus, the dependence between the two countries, though real, runs in both directions. Furthermore, over the last two decades, the Kazakhstani nuclear industry has done well to diversify its foreign partnerships. The most recent announcement by Kazakhstan that the new NPP would be built by a consortium of partners shows that this multi-vector approach has been maintained, making Kazakhstan more conscientious in terms of supplier diversification than, for instance, Hungary and Turkey.

Once a NPP is built, fuel dependence rarely becomes an issue. The high energy density and solid state of nuclear fuel makes it relatively simple to stockpile in advance, thus negating the threat of a fuel cutoff. The risk is further reduced by Kazakhstan’s recent acquisition of fuel assembly fabrication capability. With the IAEA having established an international LEU fuel bank in Kazakhstan, Russia cannot easily threaten to cut it off from supplies of enriched uranium. Conversion services are available to Kazatomprom through commercial partners both in China and in Western countries. Natural uranium, of course, can be mined from Kazakhstan’s own abundant sources. In short, a combination of mutual interdependence and alternative availability means that overdependence in terms of technology and fuel supply is fairly unlikely. One potential source of uncertainty, however, is the prospect of financial dependence if Kazakhstan were to require a loan from Russia, or, for that matter, any other state behind the deal, to finance construction. In that case, Kazakhstani stakeholders may be able to diversify financing sources, leveraging regional development banks as well as foreign investors.

Low-enriched uranium is delivered to the IAEA fuel bank in Kazakhstan | Source: Kazakhstani Foreign Ministry/World Nuclear News

7. Does China’s involvement in Kazakhstan’s civil nuclear sector have anything to do with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)?

Chinese government and corporate representatives have referred to civil nuclear cooperation projects with Kazakhstan as an integral part of the BRI. When speaking at the launch ceremony of the Kazatomprom-CGN fuel assembly fabrication plant last year, for instance, the deputy head of China’s Atomic Energy Authority praised the project as one that is “iconic” of the Belt and Road and Kazakhstan’s Nurly Zhol. This does not mean, however, that the plant was entirely a state-sponsored political project. Beneath the official rhetoric, CGN’s cooperation with Kazatomprom has in fact been driven more by corporate incentives than by the Chinese state’s foreign policy initiatives, whether prior to 2013 or after.

In the mid-2000s, both CGN and its competitor China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) began to explore JVs with Kazakhstani uranium mining entities in anticipation of the rapid expansion of nuclear generation capacity they were about to undertake. According to official statistics, the average annual growth of China’s installed nuclear capacity was 9.6% from 2005 to 2010, 20.2% from 2011 to 2015, and 13.0% from 2016 to 2020. Such a rapid nuclear energy expansion required a larger reserve of natural uranium. While CGN operates a huge reactor fleet, it is CNNC that, as the successor of China’s Ministry of Nuclear Industry, inherited the vast majority of China’s nuclear assets across other stages of the fuel cycle, from mining to assembly fabrication. To expand its services and reduce operational costs for its NPPs, CGN faced strong incentives to secure cheap uranium reserves and assembly fabrication capacity abroad. These commercial incentives, in turn, drove the corporation to pursue mining ventures in Kazakhstan and elsewhere. The deals that came after, including the purchase of fuel pellets from Kazakhstan and joint investment in the assembly fabrication plant, are logical extensions of cooperative ties long predating the inception of the BRI.

8. Are common critiques associated with the Belt and Road – such as “debt traps” and exploitative resource extraction – evident in China’s engagement of the Kazakhstani civil nuclear sector?

Chinese state-owned corporations have engaged in uranium extraction in Kazakhstan, but only through JVs with Kazatomprom – just like Canadian and Japanese companies. And the general pattern of cooperation pursued, namely, trading investment and technology for uranium access, often serves mutual interests. Indeed, the Ulba fuel assembly fabrication plant, which China helped finance and whose products are purchased by CGN, made Kazakhstan one of the few countries in the world capable of exporting high value-added fuel assemblies, in full accordance with Kazakhstan’s own nuclear industry development objectives as stated in official documents.

In June of 2014, six months before the signing of the framework agreement on the assembly fabrication plant, the Kazakhstani government released a 2030 energy sector development plan in which the acquisition of assembly fabrication technology was listed as an explicit objective. Acknowledging the country’s lack of assembly fabrication capacity, which restricted the nuclear industry to the export of low value-added natural uranium under highly volatile prices, the plan specifically called for the construction of fabrication facilities through JVs with foreign partners. Joint ventures, according to the plan, not only allow the sharing of investment burdens and associated risks, but also ensure accelerated technology transfer, personnel training, certification, and market entry. East Asian countries are singled out as the most promising markets for fuel assemblies given their rapidly growing demand.

In other words, CGN’s investment in the Ulba assembly fabrication plant filled a strategic need of the Kazakhstani civil nuclear industry – and in a mode that Kazakhstani policymakers saw as optimal. Rather than simply exploiting Kazakhstan’s raw uranium resources, the Chinese corporation helped reduce the share of low value-added extractive activities in the portfolio of Kazakhstan’s nuclear industry. Before the construction of the plant, CGN and Kazatomprom cooperated according to the same division of labor Soviet planners defined for Kazakhstan’s uranium industry. A uranium mine in Kazakhstan operated through a JV with CGN such as Semizbai-U would export natural uranium products to China to undergo conversion and enrichment, only for the end product to be shipped back to Kazakhstan to be manufactured into fuel pellets, which, in turn, are supplied as inputs to Chinese fuel assembly fabrication facilities. Now, with Kazakhstan’s own assembly fabrication plant having come online, the value added by the final stage is effectively transferred to Kazakhstan.

Whether in mining activities or in fabrication plant construction, Chinese funds have been introduced in the form of JV equity, which would have been a poor way of setting up a “debt trap,” had that been the intention. For NPP construction in the future, the mode of collaboration is yet to be seen. Given the huge long-term investment required for a typical NPP project, it is customary for governments backing the deal to offer financing in loans. That is to say, Russia and China are not the only states that offer government-backed financing to win NPP projects abroad. The United States, for instance, has used a combination of state financing and diplomatic clout to secure nuclear projects abroad. Such behavior is driven by both geostrategic interests and domestic nuclear industry lobbying. Kazakhstan, if it is to finance its NPP project using foreign state loans, would do well to avoid financial overdependence regardless of the partner it selects.

9. To what extent is the Kazakhstani nuclear sector becoming an arena of Russia-China competition?

China’s engagement has made the Kazakhstani civil nuclear industry less dependent on its partnership with Russia. Not only has China offered an alternative source of conversion and enrichment services for Kazakhstan’s natural uranium, but it has also become an alternative transit country for Kazakhstani uranium exports destined for Western countries, thus allowing Kazakhstan to diversify its supply routes away from Russia. In that sense, the competition is real.

With that said, observers who characterize Sino-Russian competition over Kazakhstan’s uranium resources and nuclear energy market as “the most heated conflict of competing strategic interests” between the two countries in the Central Asia/Caucasus region are likely overstating their case. As already discussed, the drivers of nuclear-sector engagement, at least for Chinese state-owned enterprises, are more commercial than geostrategic. Furthermore, there is no common market for nuclear energy – akin to what Europe instituted through Euratom – within the framework of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). Russia and Kazakhstan cooperate in the civil nuclear sector through ad-hoc bilateral agreements, not under a strategic vision for integration.

Russia and China have a long history of cooperation in the civil nuclear sector, and their nuclear industry stakeholders have repeatedly signaled a desire to cooperate in third countries. While much of the rhetoric has not materialized, it is clear in the case of the Kazakhstan that entities from the two countries often carry out complementary – rather than competing – fuel cycle activities. For instance, the aforementioned Russian-Kazakhstani joint venture UEC, which supplies Kazakhstan with Russian enriched uranium, has now become a supplier of the Ulba fuel assembly fabrication plant, meaning the Kazatomprom-CGN JV is using Russian enriched uranium to fabricate fuel assemblies for Chinese reactors.

If Kazakhstan does proceed with its NPP project, greater commercial competition could indeed result, but with little risk of spilling over into the geopolitical sphere. Given the international state of affairs, it is difficult to imagine Russia and China alienating each other over marginal interests in Central Asia, and an infrastructure deal, however profitable, is marginal to the overall picture, especially if the motives behind the deal are overwhelmingly commercial.

10. Now that the West has imposed unprecedented sanctions on Russia, will Kazakhstan face challenges maintaining its civil nuclear ties with entities on both sides of the geopolitical divide?

To date, Russia’s civil nuclear sector has largely escaped direct sanctions from the West. Even Hungary and Turkey, which are members of NATO, have not renounced their nuclear energy projects with Rosatom. Kazakhstan, similarly, is striving to maintain its ties with Russia in the civil nuclear sector as it has much to lose in a scenario of decoupling. Nevertheless, the secondary impacts of Western sanctions, including logistics disruptions, are compelling decision-makers of the Kazakhstani nuclear industry to seek alternative solutions.

Prior to the sanctions imposed this year, much of the uranium products Kazakhstan exported to Western countries was transported by rail to the port of St. Petersburg and shipped onward. Now, such shipments are becoming more difficult due to logistics disruptions such as the cancellation of cargo insurance for vessels leaving from Russian ports. Canadian company Cameco has announced a temporary halt to the shipment of uranium products from Kazakhstan until the finalization of “an alternative route avoiding Russian railway lines.” Kazatomprom, on the other hand, said it was not having trouble with its own shipments but admitted that it was “working to reinforce its alternative Caspian Sea route” bypassing Russia.

At the moment, much remains uncertain as to whether direct sanctions will be imposed on the Russian nuclear industry. If so, Kazakhstan will have to find some way to ensure that they do not impact its multitude of ties with Russian nuclear enterprises. Given the deep entanglement between Russia and Kazakhstan in the civil nuclear sector, complete decoupling will be nearly impossible in the near term. The risk of collateral damage on as crucial a global uranium supplier as Kazakhstan may constitute one more reason for Western countries to carefully consider, if not refrain from, targeting Russia’s civil nuclear infrastructure in their next round of sanctions. Unfortunately, such restraint will be increasingly difficult to maintain if the conflict in Ukraine continues to escalate. Caught among forces much larger than itself, the Kazakhstani nuclear industry may have no choice but to brace for impact.